# 第 11 章 Systems

by Dr. Kevin Dean Wampler

“Complexity kills. It sucks the life out of developers, it makes products difficult to plan, build, and test.”

—Ray Ozzie, CTO, Microsoft Corporation

HOW WOULD YOU BUILD A CITY? Could you manage all the details yourself? Probably not. Even managing an existing city is too much for one person. Yet, cities work (most of the time). They work because cities have teams of people who manage particular parts of the city, the water systems, power systems, traffic, law enforcement, building codes, and so forth. Some of those people are responsible for the big picture, while others focus on the details.

Cities also work because they have evolved appropriate levels of abstraction and modularity that make it possible for individuals and the “components” they manage to work effectively, even without understanding the big picture.

Although software teams are often organized like that too, the systems they work on often don’t have the same separation of concerns and levels of abstraction. Clean code helps us achieve this at the lower levels of abstraction. In this chapter let us consider how to stay clean at higher levels of abstraction, the system level.

SEPARATE CONSTRUCTING A SYSTEM FROM USING IT First, consider that construction is a very different process from use. As I write this, there is a new hotel under construction that I see out my window in Chicago. Today it is a bare concrete box with a construction crane and elevator bolted to the outside. The busy people there all wear hard hats and work clothes. In a year or so the hotel will be finished. The crane and elevator will be gone. The building will be clean, encased in glass window walls and attractive paint. The people working and staying there will look a lot different too.

Software systems should separate the startup process, when the application objects are constructed and the dependencies are “wired” together, from the runtime logic that takes over after startup.

The startup process is a concern that any application must address. It is the first concern that we will examine in this chapter. The separation of concerns is one of the oldest and most important design techniques in our craft.

Unfortunately, most applications don’t separate this concern. The code for the startup process is ad hoc and it is mixed in with the runtime logic. Here is a typical example:

public Service getService() {

if (service == null)

service = new MyServiceImpl(…); // Good enough default for most cases?

return service;

}

This is the LAZY INITIALIZATION/EVALUATION idiom, and it has several merits. We don’t incur the overhead of construction unless we actually use the object, and our startup times can be faster as a result. We also ensure that null is never returned.

However, we now have a hard-coded dependency on MyServiceImpl and everything its constructor requires (which I have elided). We can’t compile without resolving these dependencies, even if we never actually use an object of this type at runtime!

Testing can be a problem. If MyServiceImpl is a heavyweight object, we will need to make sure that an appropriate TEST DOUBLE1 or MOCK OBJECT gets assigned to the service field before this method is called during unit testing. Because we have construction logic mixed in with normal runtime processing, we should test all execution paths (for example, the null test and its block). Having both of these responsibilities means that the method is doing more than one thing, so we are breaking the Single Responsibility Principle in a small way.

- [Mezzaros07].

Perhaps worst of all, we do not know whether MyServiceImpl is the right object in all cases. I implied as much in the comment. Why does the class with this method have to know the global context? Can we ever really know the right object to use here? Is it even possible for one type to be right for all possible contexts?

One occurrence of LAZY-INITIALIZATION isn’t a serious problem, of course. However, there are normally many instances of little setup idioms like this in applications. Hence, the global setup strategy (if there is one) is scattered across the application, with little modularity and often significant duplication.

If we are diligent about building well-formed and robust systems, we should never let little, convenient idioms lead to modularity breakdown. The startup process of object construction and wiring is no exception. We should modularize this process separately from the normal runtime logic and we should make sure that we have a global, consistent strategy for resolving our major dependencies.

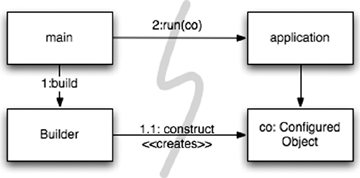

Separation of Main One way to separate construction from use is simply to move all aspects of construction to main, or modules called by main, and to design the rest of the system assuming that all objects have been constructed and wired up appropriately. (See Figure 11-1.)

The flow of control is easy to follow. The main function builds the objects necessary for the system, then passes them to the application, which simply uses them. Notice the direction of the dependency arrows crossing the barrier between main and the application. They all go one direction, pointing away from main. This means that the application has no knowledge of main or of the construction process. It simply expects that everything has been built properly.

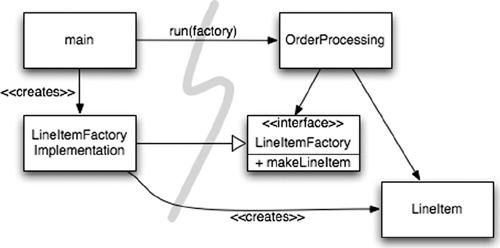

Factories Sometimes, of course, we need to make the application responsible for when an object gets created. For example, in an order processing system the application must create the

Figure 11-1 Separating construction in main()

LineItem instances to add to an Order. In this case we can use the ABSTRACT FACTORY2 pattern to give the application control of when to build the LineItems, but keep the details of that construction separate from the application code. (See Figure 11-2.)

- [GOF].

Figure 11-2 Separation construction with factory

Again notice that all the dependencies point from main toward the OrderProcessing application. This means that the application is decoupled from the details of how to build a LineItem. That capability is held in the LineItemFactoryImplementation, which is on the main side of the line. And yet the application is in complete control of when the LineItem instances get built and can even provide application-specific constructor arguments.

Dependency Injection A powerful mechanism for separating construction from use is Dependency Injection (DI), the application of Inversion of Control (IoC) to dependency management.3 Inversion of Control moves secondary responsibilities from an object to other objects that are dedicated to the purpose, thereby supporting the Single Responsibility Principle. In the context of dependency management, an object should not take responsibility for instantiating dependencies itself. Instead, it should pass this responsibility to another “authoritative” mechanism, thereby inverting the control. Because setup is a global concern, this authoritative mechanism will usually be either the “main” routine or a special-purpose container.

- See, for example, [Fowler].

JNDI lookups are a “partial” implementation of DI, where an object asks a directory server to provide a “service” matching a particular name.

MyService myService = (MyService)(jndiContext.lookup(“NameOfMyService”));

The invoking object doesn’t control what kind of object is actually returned (as long it implements the appropriate interface, of course), but the invoking object still actively resolves the dependency.

True Dependency Injection goes one step further. The class takes no direct steps to resolve its dependencies; it is completely passive. Instead, it provides setter methods or constructor arguments (or both) that are used to inject the dependencies. During the construction process, the DI container instantiates the required objects (usually on demand) and uses the constructor arguments or setter methods provided to wire together the dependencies. Which dependent objects are actually used is specified through a configuration file or programmatically in a special-purpose construction module.

The Spring Framework provides the best known DI container for Java.4 You define which objects to wire together in an XML configuration file, then you ask for particular objects by name in Java code. We will look at an example shortly.

- See [Spring]. There is also a Spring.NET framework.

But what about the virtues of LAZY-INITIALIZATION? This idiom is still sometimes useful with DI. First, most DI containers won’t construct an object until needed. Second, many of these containers provide mechanisms for invoking factories or for constructing proxies, which could be used for LAZY-EVALUATION and similar optimizations.5

- Don’t forget that lazy instantiation/evaluation is just an optimization and perhaps premature!

SCALING UP Cities grow from towns, which grow from settlements. At first the roads are narrow and practically nonexistent, then they are paved, then widened over time. Small buildings and empty plots are filled with larger buildings, some of which will eventually be replaced with skyscrapers.

At first there are no services like power, water, sewage, and the Internet (gasp!). These services are also added as the population and building densities increase.

This growth is not without pain. How many times have you driven, bumper to bumper through a road “improvement” project and asked yourself, “Why didn’t they build it wide enough the first time!?”

But it couldn’t have happened any other way. Who can justify the expense of a six-lane highway through the middle of a small town that anticipates growth? Who would want such a road through their town?

It is a myth that we can get systems “right the first time.” Instead, we should implement only today’s stories, then refactor and expand the system to implement new stories tomorrow. This is the essence of iterative and incremental agility. Test-driven development, refactoring, and the clean code they produce make this work at the code level.

But what about at the system level? Doesn’t the system architecture require preplanning? Certainly, it can’t grow incrementally from simple to complex, can it?

Software systems are unique compared to physical systems. Their architectures can grow incrementally, ifwe maintain the proper separation of concerns.

The ephemeral nature of software systems makes this possible, as we will see. Let us first consider a counterexample of an architecture that doesn’t separate concerns adequately.

The original EJB1 and EJB2 architectures did not separate concerns appropriately and thereby imposed unnecessary barriers to organic growth. Consider an Entity Bean for a persistent Bank class. An entity bean is an in-memory representation of relational data, in other words, a table row.

First, you had to define a local (in process) or remote (separate JVM) interface, which clients would use. Listing 11-1 shows a possible local interface:

Listing 11-1 An EJB2 local interface for a Bank EJB

package com.example.banking;

import java.util.Collections;

import javax.ejb.*;

public interface BankLocal extends java.ejb.EJBLocalObject {

String getStreetAddr1() throws EJBException;

String getStreetAddr2() throws EJBException;

String getCity() throws EJBException;

String getState() throws EJBException;

String getZipCode() throws EJBException;

void setStreetAddr1(String street1) throws EJBException;

void setStreetAddr2(String street2) throws EJBException;

void setCity(String city) throws EJBException;

void setState(String state) throws EJBException;

void setZipCode(String zip) throws EJBException;

Collection getAccounts() throws EJBException;

void setAccounts(Collection accounts) throws EJBException;

void addAccount(AccountDTO accountDTO) throws EJBException;

}

I have shown several attributes for the Bank’s address and a collection of accounts that the bank owns, each of which would have its data handled by a separate Account EJB. Listing 11-2 shows the corresponding implementation class for the Bank bean.

Listing 11-2 The corresponding EJB2 Entity Bean Implementation

package com.example.banking;

import java.util.Collections;

import javax.ejb.*;

public abstract class Bank implements javax.ejb.EntityBean {

// Business logic…

public abstract String getStreetAddr1();

public abstract String getStreetAddr2();

public abstract String getCity();

public abstract String getState();

public abstract String getZipCode();

public abstract void setStreetAddr1(String street1);

public abstract void setStreetAddr2(String street2);

public abstract void setCity(String city);

public abstract void setState(String state);

public abstract void setZipCode(String zip);

public abstract Collection getAccounts();

public abstract void setAccounts(Collection accounts);

public void addAccount(AccountDTO accountDTO) {

InitialContext context = new InitialContext();

AccountHomeLocal accountHome = context.lookup(”AccountHomeLocal”);

AccountLocal account = accountHome.create(accountDTO);

Collection accounts = getAccounts();

accounts.add(account);

}

// EJB container logic

public abstract void setId(Integer id);

public abstract Integer getId();

public Integer ejbCreate(Integer id) { … }

public void ejbPostCreate(Integer id) { … }

// The rest had to be implemented but were usually empty:

public void setEntityContext(EntityContext ctx) {}

public void unsetEntityContext() {}

public void ejbActivate() {}

public void ejbPassivate() {}

public void ejbLoad() {}

public void ejbStore() {}

public void ejbRemove() {}

}

I haven’t shown the corresponding LocalHome interface, essentially a factory used to create objects, nor any of the possible Bank finder (query) methods you might add.

Finally, you had to write one or more XML deployment descriptors that specify the object-relational mapping details to a persistence store, the desired transactional behavior, security constraints, and so on.

The business logic is tightly coupled to the EJB2 application “container.” You must subclass container types and you must provide many lifecycle methods that are required by the container.

Because of this coupling to the heavyweight container, isolated unit testing is difficult. It is necessary to mock out the container, which is hard, or waste a lot of time deploying EJBs and tests to a real server. Reuse outside of the EJB2 architecture is effectively impossible, due to the tight coupling.

Finally, even object-oriented programming is undermined. One bean cannot inherit from another bean. Notice the logic for adding a new account. It is common in EJB2 beans to define “data transfer objects” (DTOs) that are essentially “structs” with no behavior. This usually leads to redundant types holding essentially the same data, and it requires boilerplate code to copy data from one object to another.

Cross-Cutting Concerns The EJB2 architecture comes close to true separation of concerns in some areas. For example, the desired transactional, security, and some of the persistence behaviors are declared in the deployment descriptors, independently of the source code.

Note that concerns like persistence tend to cut across the natural object boundaries of a domain. You want to persist all your objects using generally the same strategy, for example, using a particular DBMS6 versus flat files, following certain naming conventions for tables and columns, using consistent transactional semantics, and so on.

- Database management system.

In principle, you can reason about your persistence strategy in a modular, encapsulated way. Yet, in practice, you have to spread essentially the same code that implements the persistence strategy across many objects. We use the term cross-cutting concerns for concerns like these. Again, the persistence framework might be modular and our domain logic, in isolation, might be modular. The problem is the fine-grained intersection of these domains.

In fact, the way the EJB architecture handled persistence, security, and transactions, “anticipated” aspect-oriented programming (AOP),7 which is a general-purpose approach to restoring modularity for cross-cutting concerns.

- See [AOSD] for general information on aspects and [AspectJ]] and [Colyer] for AspectJ-specific information.

In AOP, modular constructs called aspects specify which points in the system should have their behavior modified in some consistent way to support a particular concern. This specification is done using a succinct declarative or programmatic mechanism.

Using persistence as an example, you would declare which objects and attributes (or patterns thereof) should be persisted and then delegate the persistence tasks to your persistence framework. The behavior modifications are made noninvasively8 to the target code by the AOP framework. Let us look at three aspects or aspect-like mechanisms in Java.

- Meaning no manual editing of the target source code is required.

JAVA PROXIES Java proxies are suitable for simple situations, such as wrapping method calls in individual objects or classes. However, the dynamic proxies provided in the JDK only work with interfaces. To proxy classes, you have to use a byte-code manipulation library, such as CGLIB, ASM, or Javassist.9

- See [CGLIB], [ASM], and [Javassist].

Listing 11-3 shows the skeleton for a JDK proxy to provide persistence support for our Bank application, covering only the methods for getting and setting the list of accounts.

Listing 11-3 JDK Proxy Example

// Bank.java (suppressing package names…)

import java.utils.*;

// The abstraction of a bank.

public interface Bank {

Collection<Account> getAccounts();

void setAccounts(Collection<Account> accounts);

}

// BankImpl.java

import java.utils.*;

// The “Plain Old Java Object” (POJO) implementing the abstraction.

public class BankImpl implements Bank {

private List<Account> accounts;

public Collection<Account> getAccounts() {

return accounts;

}

public void setAccounts(Collection<Account> accounts) {

this.accounts = new ArrayList<Account>();

for (Account account: accounts) {

this.accounts.add(account);

}

}

}

// BankProxyHandler.java

import java.lang.reflect.*;

import java.util.*;

// “InvocationHandler” required by the proxy API.

public class BankProxyHandler implements InvocationHandler {

private Bank bank;

public BankHandler (Bank bank) {

this.bank = bank;

}

// Method defined in InvocationHandler

public Object invoke(Object proxy, Method method, Object[] args)

throws Throwable {

String methodName = method.getName();

if (methodName.equals(”getAccounts”)) {

bank.setAccounts(getAccountsFromDatabase());

return bank.getAccounts();

} else if (methodName.equals(”setAccounts”)) {

bank.setAccounts((Collection<Account>) args[0]);

setAccountsToDatabase(bank.getAccounts());

return null;

} else {

…

}

}

// Lots of details here:

protected Collection<Account> getAccountsFromDatabase() { … }

protected void setAccountsToDatabase(Collection<Account> accounts) { … }

}

// Somewhere else…

Bank bank = (Bank) Proxy.newProxyInstance(

Bank.class.getClassLoader(),

new Class[] { Bank.class },

new BankProxyHandler(new BankImpl()));

We defined an interface Bank, which will be wrapped by the proxy, and a Plain-Old Java Object (POJO), BankImpl, that implements the business logic. (We will revisit POJOs shortly.)

The Proxy API requires an InvocationHandler object that it calls to implement any Bank method calls made to the proxy. Our BankProxyHandler uses the Java reflection API to map the generic method invocations to the corresponding methods in BankImpl, and so on.

There is a lot of code here and it is relatively complicated, even for this simple case.10 Using one of the byte-manipulation libraries is similarly challenging. This code “volume”

- For more detailed examples of the Proxy API and examples of its use, see, for example, [Goetz].

and complexity are two of the drawbacks of proxies. They make it hard to create clean code! Also, proxies don’t provide a mechanism for specifying system-wide execution “points” of interest, which is needed for a true AOP solution.11

- AOP is sometimes confused with techniques used to implement it, such as method interception and “wrapping” through proxies. The real value of an AOP system is the ability to specify systemic behaviors in a concise and modular way.

PURE JAVA AOP FRAMEWORKS Fortunately, most of the proxy boilerplate can be handled automatically by tools. Proxies are used internally in several Java frameworks, for example, Spring AOP and JBoss AOP, to implement aspects in pure Java.12 In Spring, you write your business logic as Plain-Old Java Objects. POJOs are purely focused on their domain. They have no dependencies on enterprise frameworks (or any other domains). Hence, they are conceptually simpler and easier to test drive. The relative simplicity makes it easier to ensure that you are implementing the corresponding user stories correctly and to maintain and evolve the code for future stories.

- See [Spring] and [JBoss]. “Pure Java” means without the use of AspectJ.

You incorporate the required application infrastructure, including cross-cutting concerns like persistence, transactions, security, caching, failover, and so on, using declarative configuration files or APIs. In many cases, you are actually specifying Spring or JBoss library aspects, where the framework handles the mechanics of using Java proxies or byte-code libraries transparently to the user. These declarations drive the dependency injection (DI) container, which instantiates the major objects and wires them together on demand.

Listing 11-4 shows a typical fragment of a Spring V2.5 configuration file, app.xml13:

- Adapted from http://www.theserverside.com/tt/articles/article.tss?l=IntrotoSpring25.

Listing 11-4 Spring 2.X configuration file

<beans>

…

<bean id=”appDataSource”

class=”org.apache.commons.dbcp.BasicDataSource”

destroy-method=”close”

p:driverClassName=”com.mysql.jdbc.Driver”

p:url=”jdbc:mysql://localhost:3306/mydb”

p:username=”me”/>

<bean id=”bankDataAccessObject”

class=”com.example.banking.persistence.BankDataAccessObject”

p:dataSource-ref=”appDataSource”/>

<bean id=”bank”

class=”com.example.banking.model.Bank”

p:dataAccessObject-ref=”bankDataAccessObject”/>

…

</beans>

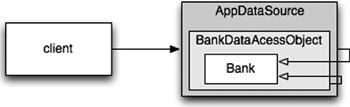

Each “bean” is like one part of a nested “Russian doll,” with a domain object for a Bank proxied (wrapped) by a data accessor object (DAO), which is itself proxied by a JDBC driver data source. (See Figure 11-3.)

Figure 11-3 The “Russian doll” of decorators

The client believes it is invoking getAccounts() on a Bank object, but it is actually talking to the outermost of a set of nested DECORATOR14 objects that extend the basic behavior of the Bank POJO. We could add other decorators for transactions, caching, and so forth.

- [GOF].

In the application, a few lines are needed to ask the DI container for the top-level objects in the system, as specified in the XML file.

XmlBeanFactory bf =

new XmlBeanFactory(new ClassPathResource(”app.xml”, getClass()));

Bank bank = (Bank) bf.getBean(”bank”);

Because so few lines of Spring-specific Java code are required, the application is almost completely decoupled from Spring, eliminating all the tight-coupling problems of systems like EJB2.

Although XML can be verbose and hard to read,15 the “policy” specified in these configuration files is simpler than the complicated proxy and aspect logic that is hidden from view and created automatically. This type of architecture is so compelling that frameworks like Spring led to a complete overhaul of the EJB standard for version 3. EJB3

- The example can be simplified using mechanisms that exploit convention over configuration and Java 5 annotations to reduce the amount of explicit “wiring” logic required.

largely follows the Spring model of declaratively supporting cross-cutting concerns using XML configuration files and/or Java 5 annotations.

Listing 11-5 shows our Bank object rewritten in EJB316.

- Adapted from http://www.onjava.com/pub/a/onjava/2006/05/17/standardizing-with-ejb3-java-persistence-api.html

Listing 11-5 An EBJ3 Bank EJB

package com.example.banking.model;

import javax.persistence.*;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Collection;

@Entity

@Table(name = “BANKS”)

public class Bank implements java.io.Serializable {

@Id @GeneratedValue(strategy=GenerationType.AUTO)

private int id;

@Embeddable // An object “inlined” in Bank’s DB row

public class Address {

protected String streetAddr1;

protected String streetAddr2;

protected String city;

protected String state;

protected String zipCode;

}

@Embedded

private Address address;

@OneToMany(cascade = CascadeType.ALL, fetch = FetchType.EAGER,

mappedBy=”bank”)

private Collection<Account> accounts = new ArrayList<Account>();

public int getId() {

return id;

}

public void setId(int id) {

this.id = id;

}

public void addAccount(Account account) {

account.setBank(this);

accounts.add(account);

}

public Collection<Account> getAccounts() {

return accounts;

}

public void setAccounts(Collection<Account> accounts) {

this.accounts = accounts;

}

}

This code is much cleaner than the original EJB2 code. Some of the entity details are still here, contained in the annotations. However, because none of that information is outside of the annotations, the code is clean, clear, and hence easy to test drive, maintain, and so on.

Some or all of the persistence information in the annotations can be moved to XML deployment descriptors, if desired, leaving a truly pure POJO. If the persistence mapping details won’t change frequently, many teams may choose to keep the annotations, but with far fewer harmful drawbacks compared to the EJB2 invasiveness.

ASPECTJ ASPECTS Finally, the most full-featured tool for separating concerns through aspects is the AspectJ language,17 an extension of Java that provides “first-class” support for aspects as modularity constructs. The pure Java approaches provided by Spring AOP and JBoss AOP are sufficient for 80–90 percent of the cases where aspects are most useful. However, AspectJ provides a very rich and powerful tool set for separating concerns. The drawback of AspectJ is the need to adopt several new tools and to learn new language constructs and usage idioms.

- See [AspectJ] and [Colyer].

The adoption issues have been partially mitigated by a recently introduced “annotation form” of AspectJ, where Java 5 annotations are used to define aspects using pure Java code. Also, the Spring Framework has a number of features that make incorporation of annotation-based aspects much easier for a team with limited AspectJ experience.

A full discussion of AspectJ is beyond the scope of this book. See [AspectJ], [Colyer], and [Spring] for more information.

TEST DRIVE THE SYSTEM ARCHITECTURE The power of separating concerns through aspect-like approaches can’t be overstated. If you can write your application’s domain logic using POJOs, decoupled from any architecture concerns at the code level, then it is possible to truly test drive your architecture. You can evolve it from simple to sophisticated, as needed, by adopting new technologies on demand. It is not necessary to do a Big Design Up Front18 (BDUF). In fact, BDUF is even harmful because it inhibits adapting to change, due to the psychological resistance to discarding prior effort and because of the way architecture choices influence subsequent thinking about the design.

- Not to be confused with the good practice of up-front design, BDUF is the practice of designing everything up front before implementing anything at all.

Building architects have to do BDUF because it is not feasible to make radical architectural changes to a large physical structure once construction is well underway.19 Although software has its own physics,20 it is economically feasible to make radical change, if the structure of the software separates its concerns effectively.

There is still a significant amount of iterative exploration and discussion of details, even after construction starts.

The term software physics was first used by [Kolence].

This means we can start a software project with a “naively simple” but nicely decoupled architecture, delivering working user stories quickly, then adding more infrastructure as we scale up. Some of the world’s largest Web sites have achieved very high availability and performance, using sophisticated data caching, security, virtualization, and so forth, all done efficiently and flexibly because the minimally coupled designs are appropriately simple at each level of abstraction and scope.

Of course, this does not mean that we go into a project “rudderless.” We have some expectations of the general scope, goals, and schedule for the project, as well as the general structure of the resulting system. However, we must maintain the ability to change course in response to evolving circumstances.

The early EJB architecture is but one of many well-known APIs that are over-engineered and that compromise separation of concerns. Even well-designed APIs can be overkill when they aren’t really needed. A good API should largely disappear from view most of the time, so the team expends the majority of its creative efforts focused on the user stories being implemented. If not, then the architectural constraints will inhibit the efficient delivery of optimal value to the customer.

To recap this long discussion,

An optimal system architecture consists of modularized domains of concern, each of which is implemented with Plain Old Java (or other) Objects. The different domains are integrated together with minimally invasive Aspects or Aspect-like tools. This architecture can be test-driven, just like the code.

OPTIMIZE DECISION MAKING Modularity and separation of concerns make decentralized management and decision making possible. In a sufficiently large system, whether it is a city or a software project, no one person can make all the decisions.

We all know it is best to give responsibilities to the most qualified persons. We often forget that it is also best to postpone decisions until the last possible moment. This isn’t lazy or irresponsible; it lets us make informed choices with the best possible information. A premature decision is a decision made with suboptimal knowledge. We will have that much less customer feedback, mental reflection on the project, and experience with our implementation choices if we decide too soon.

The agility provided by a POJO system with modularized concerns allows us to make optimal, just-in-time decisions, based on the most recent knowledge. The complexity of these decisions is also reduced.

USE STANDARDS WISELY, WHEN THEY ADD DEMONSTRABLE VALUE Building construction is a marvel to watch because of the pace at which new buildings are built (even in the dead of winter) and because of the extraordinary designs that are possible with today’s technology. Construction is a mature industry with highly optimized parts, methods, and standards that have evolved under pressure for centuries.

Many teams used the EJB2 architecture because it was a standard, even when lighter-weight and more straightforward designs would have been sufficient. I have seen teams become obsessed with various strongly hyped standards and lose focus on implementing value for their customers.

Standards make it easier to reuse ideas and components, recruit people with relevant experience, encapsulate good ideas, and wire components together. However, the process of creating standards can sometimes take too long for industry to wait, and some standards lose touch with the real needs of the adopters they are intended to serve.

SYSTEMS NEED DOMAIN-SPECIFIC LANGUAGES Building construction, like most domains, has developed a rich language with a vocabulary, idioms, and patterns21 that convey essential information clearly and concisely. In software, there has been renewed interest recently in creating Domain-Specific Languages (DSLs),22 which are separate, small scripting languages or APIs in standard languages that permit code to be written so that it reads like a structured form of prose that a domain expert might write.

The work of [Alexander] has been particularly influential on the software community.

See, for example, [DSL]. [JMock] is a good example of a Java API that creates a DSL.

A good DSL minimizes the “communication gap” between a domain concept and the code that implements it, just as agile practices optimize the communications within a team and with the project’s stakeholders. If you are implementing domain logic in the same language that a domain expert uses, there is less risk that you will incorrectly translate the domain into the implementation.

DSLs, when used effectively, raise the abstraction level above code idioms and design patterns. They allow the developer to reveal the intent of the code at the appropriate level of abstraction.

Domain-Specific Languages allow all levels of abstraction and all domains in the application to be expressed as POJOs, from high-level policy to low-level details.

CONCLUSION Systems must be clean too. An invasive architecture overwhelms the domain logic and impacts agility. When the domain logic is obscured, quality suffers because bugs find it easier to hide and stories become harder to implement. If agility is compromised, productivity suffers and the benefits of TDD are lost.

At all levels of abstraction, the intent should be clear. This will only happen if you write POJOs and you use aspect-like mechanisms to incorporate other implementation concerns noninvasively.

Whether you are designing systems or individual modules, never forget to use the simplest thing that can possibly work.